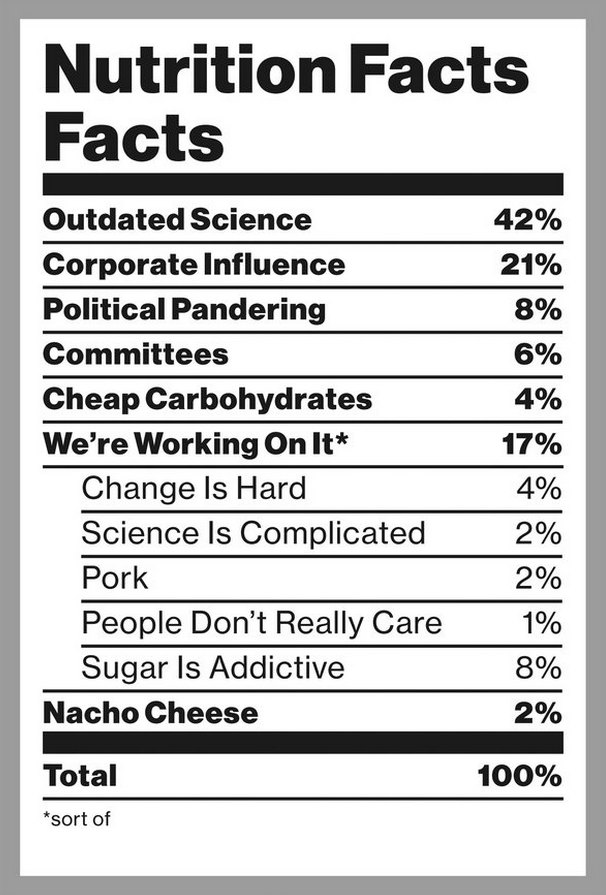

BOSTON — SINCE the publication of the federal government’s 1980 Dietary Guidelines, dietary policy has focused on reducing total fat in the American diet — specifically, to no more than 30 percent of a person’s daily calories. This fear of fat has had far-reaching impacts, from consumer preferences to the billions of dollars spent by the military, government-run hospitals and school districts on food. As we argue in a recently published article in The Journal of the American Medical Association, 35 years after that policy shift, it’s long past time for us to exonerate dietary fat.

The guidelines changed how Americans eat. By the mid-1990s, a flood of low-fat products entered the food supply: nonfat salad dressing, baked potato chips, low-fat sweetened milk and yogurt and low-fat processed turkey and bologna. Take fat-free SnackWell’s cookies. In 1994, only two years after being introduced, SnackWell’s skyrocketed to become America’s No. 1 cookie, displacing Oreos, a favorite for more than 80 years.

In place of fat, we were told to eat more carbohydrates. Indeed, carbohydrates were positioned as the foundation of a healthy diet: The 1992 edition of the food pyramid, assembled by the Department of Agriculture, recommended up to 11 daily servings of bread, cereal, rice and pasta. Americans, and food companies and restaurants, listened — our consumption of fat went down and carbs, way up.

But nutrition, like any scientific field, has advanced quickly, and by 2000, the benefits of very-low-fat diets had come into question. Increasingly, the 30 percent cap on dietary fat appeared arbitrary and possibly harmful. Following an Institute of Medicine report, the 2005 Dietary Guidelines quietly began to reverse the government’s campaign against dietary fat, increasing the upper limit to 35 percent — and also, for the first time, recommending a lower limit of 20 percent.

Yet, this major change went largely unnoticed by federal food policy makers. The Nutrition Facts panel on all packaged foods continued to use, and still uses today, the older 30 percent limit on total fat. And the Food and Drug Administration continues to regulate health claims based on total fat, regardless of the food source. In March, the F.D.A. formally warned the manufacturer of Kind snack bars to stop marketing their products as “healthy” when they exceeded decades-old limits on total and saturated fat — even though the fats in these products mainly come from nuts and healthy vegetable sources.

The “We Can!” program, run by the National Institutes of Health, recommends that kids “eat almost anytime” fat-free salad dressing, ketchup, diet soda and trimmed beef, but only “eat sometimes or less often” all vegetables with added fat, nuts, peanut butter, tuna canned in oil and olive oil. Astoundingly, the National School Lunch Program bans whole milk, but allows sugar-sweetened skim milk.

Consumers didn’t notice, either. Based on years of low-fat messaging, most Americans still actively avoid dietary fat, while eating far too much refined carbohydrates. This fear of fat also drives industry formulations, with heavy marketing of fat-reduced products of dubious health value.

Recent research has established the futility of focusing on low-fat foods. Confirming many other observations, large randomized trials in 2006 and 2013 showed that a low-fat diet had no significant benefits for heart disease, stroke, diabetes or cancer risks, while a high-fat, Mediterranean-style diet rich in nuts or extra-virgin olive oil — exceeding 40 percent of calories in total fat — significantly reduced cardiovascular disease, diabetes and long-term weight gain. Other studies have shown that high-fat diets are similar to, or better than, low-fat diets for short-term weight loss, and that types of foods, rather than fat content, relate to long-term weight gain.

This is not to say that high-fat diets are always healthy, or low-fat diets always harmful. But rather than focusing on total fat or other numbers on the back of the package, the emphasis should be on eating more minimally processed fruits, nuts, vegetables, beans, fish, yogurt, vegetable oils and whole grains in place of refined grains, white potatoes, added sugars and processed meats. How much we eat is also determined by what we eat: Cutting calories without improving food quality rarely produces long-term weight loss.

Recognizing this new evidence, the scientists on the 2015 Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee, for the first time in 35 years have sent recommendations to the government without any upper limit on total fat. In addition, reduced-fat foods were specifically not recommended for obesity prevention. Instead, the committee encouraged consumption according to healthful food-based diet patterns.

The limit on total fat is an outdated concept, an obstacle to sensible change that promotes harmful low-fat foods, undermines efforts to limit refined grains and added sugars, and discourages the food industry from developing products higher in healthy fats. Fortunately, the people behind the Dietary Guidelines understand that. Will the government, policy makers and the food industry take notice this time?